This post is a summary of the comparative measurement

block-in process that I have learned from Jeremy Deck at The Cambridge St.

Studios. Footnotes are included in this post to indicate which sentences in this post are summarizations of ideas that the instructors at The Cambridge Street Studios have explained to me.

The Importance of Practicing Block-ins

The Block-in describes the outlines of an image that an artist

defines before modeling a subject. The

block-in is the foundation for modeling form.

One cannot achieve maximum accuracy of form without a completely

accurate block-in. The more accurate of

a map that one can layout to model on top of the more accurate the modeling can

be. If complete accuracy is not adhered

to in the block-in the planes that the shapes in the block-in describe will be

off and therefore the modeling on top of that block-in will not be accurate.

The practice of blocking in with an

emphasis on copying the shapes that one sees is very important. It is by copying the character of the shapes

that one sees that allows one to gain the highest accuracy in a block-in. It is no wonder that in the 19th

century, with the invention of photography that the accuracy in drawing

improved tremendously. ¹ It is not that artists were necessarily using

photography (although some artists did trace from photos) but the invention of

photography allowed for artists to see that specificity to the shapes that one sees allowed

for a higher level of accuracy.¹ It was

thought by artists prior to the 19th century that a profound

knowledge of anatomy would imbue their drawings with complete accuracy. But the copying of anatomy without building

the anatomy upon accurate representations of the shapes that one sees does not

result in accurate drawing. When only

the general idea of what accurate

anatomy looks like is applied to a block-in

the proportions that one is drawing become general as well and the practice of

blocking-in with that mindset will not result in the specific proportions of the

subject that one is copying. Take for

example this drawing by Michelangelo.

It

is completely accurate in the general idea of anatomy but no one looks like

that. If one was to follow Michelangelo’s

mode of thought one could perfectly draw the general anatomical idea of a bicep

and not draw a specific bicep seen in perspective on a specific

individual. Paying attention to the

visual shapes that anatomy conforms to on each individual seen in perspective helps to avoid this fault. Take these drawings by Bouguereau as an

example of the specific accuracy that focusing on the shapes that one is

copying allows for.

Notice how accurate

anatomy must conform to the shapes that one sees in order for a drawing to

represent a specific subject.

To ensure the most accuracy in

copying the shapes that one sees it is useful to use comparative measurement. The practice of comparative measurement

allows one to ensure that all of the shapes are accurate in relation to a

specific height to width measurement.¹ Without the use of comparative measurement and only the practice of

trying to copy the shapes that one sees through plumbing the height to width

relationship usually becomes in accurate.¹ To practice comparative measurement there are specific guidelines that

must be adhered to.

The Set- Up (please note that actual perspective was not

used in creating this diagram)

What one sees is limited to what is in one's cone of vision. A cone of vision describes the extremities of one's sight. The cone of vision spreads out equally in each direction the further it moves away from one's eye and is always parallel to one's gaze. In the diagram above the orange figure is drawing the box on the

wall and the yellow lines represent his cone of vision, the blue figure is

making a horizontal measurement of the box on the wall and the green lines

represent his cone of vision. The easel must be set-up at a perpendicular angle

to the subject so that the horizontal center of the subject is at the center of

one’s cone of vision.¹ This way one can

easily look from their drawing to the subject without having to arch their neck

or move their feet.¹ In this diagram the

drawing board is placed parallel to the orange figure’s cone of vision. If the center of one’s cone of vision is not

on the center of the drawing then the drawing could appear correct from the

angle that they are drawing at but when properly viewed by a viewer who is

parallel to the picture the proportions will look distorted.¹ This diagram also demonstrates that the angle

that measurements are made at must be parallel to the angle of one's cone of

vision. If the stick that the blue

figure in this diagram is holding was placed at a non-parallel angle to his

cone of vision, the accuracy of his measurement will be slighted by the

distortion of the angle that he is measuring on. Also note how close the orange figure is to

the subject that he is drawing. It is

advisable to get as close as possible, without distortion, when drawing because

the closer one is the crisper things look and it is easiest to draw something when one can see it as clearly as

possible.¹

Taping off the cast

This diagram illustrates what taping a vertical and

horizontal extremity that one sees of a cast does for the placement of the

cone of vision. By taping off the

horizontal and vertical extremities from the angle that one sees a cast the

cone of vision becomes cemented in a specific place.¹ In this diagram the eye can look in any

direction up, down and left to right but the eye’s position horizontally and

vertically must be fixed if one wants to ensure that they are copying the same

image each drawing session. By taping

off one’s toes one ensures that the distance of the eye from the cast remains

constant.¹ Please note that taping off

the horizontal and vertical extremities is usually only applied to cast

drawing. Although one could tape off

where they see the vertical and horizontal extremities on a figure, a figure

moves. But it is useful to tape off

one’s feet when drawing a figure.¹

Measuring (please note that actual perspective was not used in creating this diagram)

The goal of the block-in is to accurately represent the subject they are drawing as it appears on the picture plane.¹ The picture plane can be thought of as an imaginary piece of glass that one views a subject through. The viewer in the illustration above has to look up and down to see the entire box they are measuring. Since the viewer has to look up and down to see the entire box in the illustration above, the overall picture plane that contains the entire image of the large box is as curved as the arc of the viewer's eye that has to look up and down to view the entire box on the wall.¹ This is why one must make sure that the measurements for each section of their cone of vision are parallel to each section of the picture plane in order to make accurate measurements.¹

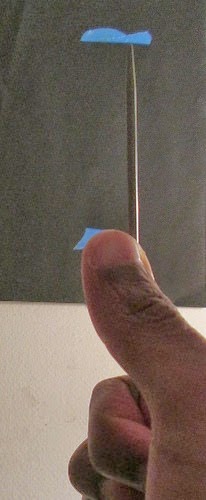

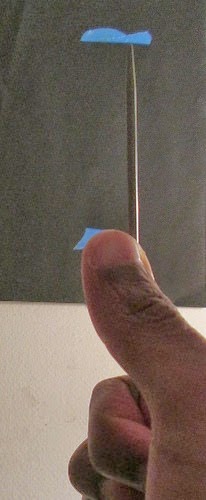

Measuring at an arm’s length helps to ensure that the distance of the picture plane that one is measuring on remains at a fixed distance from the eye.¹ It is helpful to think of the picture plane that one measures on as a sheet of glass and the block-in just as a representation of the shapes that one sees on that sheet of glass.¹ To this effect when one gets to the point where they are adding up spaces between the lines in their drawing it is helpful to think of it as tapping on the glass of the picture plane instead of just pointing in the air.¹ It is difficult to make sure that one is measuring at a completely parallel angle to their cone of vision but there is a useful trick to making this task easier. According to Andrew McManus, the measuring tool will only appear parallel to one's cone of vision when it reaches its longest length in perspective.²

Measuring at an arm’s length helps to ensure that the distance of the picture plane that one is measuring on remains at a fixed distance from the eye.¹ It is helpful to think of the picture plane that one measures on as a sheet of glass and the block-in just as a representation of the shapes that one sees on that sheet of glass.¹ To this effect when one gets to the point where they are adding up spaces between the lines in their drawing it is helpful to think of it as tapping on the glass of the picture plane instead of just pointing in the air.¹ It is difficult to make sure that one is measuring at a completely parallel angle to their cone of vision but there is a useful trick to making this task easier. According to Andrew McManus, the measuring tool will only appear parallel to one's cone of vision when it reaches its longest length in perspective.²

The example above shows how the size of the measuring tool diminishes in perspective as it is turned towards and away from one's eye, even when it is held from the same point. When the measuring tool is longest in perspective, as seen in the middle image above, it is parallel to one's cone of vision.

Keeping the measuring tool parallel to one's eye in perspective also applies to horizontal measurements as well. This is illustrated in the images above.

Keeping the measuring tool parallel to one's eye in perspective also applies to horizontal measurements as well. This is illustrated in the images above.

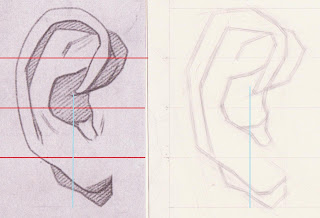

Here is a demonstration of the practice of comparative

measurement on a Bargue copy.

Block-in Step 1-The Envelope

The first step starts with measuring the actual size of the

longest dimension of the Bargue. It is

easiest to copy shapes when working at actual or sight size. So I made the length of my copy the same length

as the Bargue. Then I used a level to

mark off the top and bottom of my copy with horizontal lines. A level was also

used to make the vertical line. In comparative measurement the longest

dimension on the drawing remains fixed and it is the goal of comparative

measurement to find the measurement of the shorter dimension on the

drawing.

After this, the next step is the envelope. Using a hard sharp pencil (I usually use and H) and thick lines, made from multiple applications of the pencil to the paper, I drew lines that generally envelop the shape of the ear. By using thick sharp lines it is easy for me to use my kneaded eraser to change the sides of the lines I make when I realize that they have to be moved. To keep it simple, it is helpful to use only 3-5 lines for the envelope.¹ The order that I drew these lines in was decided by starting with the lines of the longest dimensions of the ear to get a feel for the overall mass of the shape of the envelope and I then added tilts from there.¹ This same process of laying in shapes from the longest tilts to shorter tilts is followed while laying in all of the shapes throughout the block-in process.¹ It is important to keep the lines straight throughout the entire block-in process to simplify any curves that are seen.¹ The idea is to work from general to specific so using straight lines is very helpful for that. It is also important to let the lines cross over each other throughout the entire block-in process in order to have an easier time of moving their points of intersection while re-arranging shapes.¹

After this, the next step is the envelope. Using a hard sharp pencil (I usually use and H) and thick lines, made from multiple applications of the pencil to the paper, I drew lines that generally envelop the shape of the ear. By using thick sharp lines it is easy for me to use my kneaded eraser to change the sides of the lines I make when I realize that they have to be moved. To keep it simple, it is helpful to use only 3-5 lines for the envelope.¹ The order that I drew these lines in was decided by starting with the lines of the longest dimensions of the ear to get a feel for the overall mass of the shape of the envelope and I then added tilts from there.¹ This same process of laying in shapes from the longest tilts to shorter tilts is followed while laying in all of the shapes throughout the block-in process.¹ It is important to keep the lines straight throughout the entire block-in process to simplify any curves that are seen.¹ The idea is to work from general to specific so using straight lines is very helpful for that. It is also important to let the lines cross over each other throughout the entire block-in process in order to have an easier time of moving their points of intersection while re-arranging shapes.¹

Block-in Step 2-Large Rhythms

Three lines were drawn that indicate large rhythms that run

through entire shape of the cast.

Although measuring will take care of the majority of any placement

issues I tried to be as specific about where I placed these marks because I

have found that the better I start my block-ins the smoother the process of

comparative measurement is.¹ For this

stage one can even face the Bargue and draw a line in the air with their pencil

to get a better feel of a rhythms placement within the envelope.¹ It is very useful in this stage and the previous

stage to simultaneously turn one’s head from the drawing to the Bargue while

still drawing to get a better feel for the angles that the tilts are at.¹

Block-in Step 3- Big Shapes

After I lightened my envelope and large rhythms

by rolling my kneaded eraser into a ball and rolling it on top of the drawing,

I drew the big shapes that I saw in the ear. To keep it simple, it is helpful to only use 3-6 shapes in this stage.¹ Instead of trying to draw abstract shapes or

tilts it is much easier and useful to focus on copying the character of the

shapes that one sees. A great way of

seeing the character in shapes is to think of them as the silhouettes of

cartoon animals. It is much easier to

get an impression of the character of an animal shape than that of an abstract

shape, so I proceed through the entire block-in process with referring to the

shapes that I see as animal shapes and try my best to copy the character of

them. By throwing my eyes out of focus (opening them wide enough to the point where things become slightly blurred) I can better see shapes.¹ It is useful to start with the

most obvious shape that one sees and I tried my best to place it as accurately as

possible within the envelope the I made while using the rhythms as a guide for its

placement.¹

To me this shape was a snake. To get a better idea of the character of different parts of a shape it is useful to think of a different animal shape(s) that characterizes a specific part of a shape.¹ For example, if I was having trouble imagining the snakes tail I could instead think of that area of the shape as a dogs head looking down. I used thick lines to get a general sense of

where the final thin line will be placed.

One is not supposed to think of the final thin line being placed on a

side of this thick line but one is to think of the final thin line eventually

to be placed somewhere in the middle of the thick lines.¹ Please note that while putting in the other

big shapes it is fine if they do not completely adhere to the shape of the

envelope. The envelope is just a try and

since it is usually not 100 percent accurate one must let the animal shapes be

a guide.¹ Also, it is much easier to get

straight lines when focusing on copying the character of the animal shapes

instead of copying tilts. It is very

useful to check the alignment and angles of the animal shapes throughout the

block-in process.¹ To make it easier to compare the shapes in my copy to the shapes on the Bargue I made parts of certain shapes that were not as distinct on the Bargue lighter in my copy.

Block-in Step 4- Halfway Alignment

After the big shapes have been put in I have enough

information in my block in to refer to while checking my measurements. In this stage I aligned the shapes to the halfway

mark of the longest dimension on my drawing to the halfway mark of the longest

dimension on the Bargue. Awareness of

animal shapes is at the core of this measuring process too.¹ Any adjustment to the alignment of shapes to

any measured mark must come with keeping the animal shapes in mind.¹ Since there is room for error with measuring, the animal shapes can be a great guide for letting one know if one's measurement may be off.¹

For example, if it seemed like moving an animal shape much further than

it could possibly move because one's measurement says so it becomes important to

check the measurement multiple times.

When drawing a cast one can’t really place their measuring tool on the cast to find the halfway point but one certainly should place their measuring tool on the drawing to ensure that their measuring and aligning is accurate. To do this properly one has to make sure that they are looking at the extremity of each measurement at eye level. For instance, when I was finding the halfway mark on my drawing I made sure to look at the top and bottom of the measurement on my knitting needle at eye level to make sure that I had a constant measurement.¹ I have found it more useful to mark a line on my knitting needle when trying to find these measurements instead of using my thumb. But there is no remedy for this when measuring the cast. One just has to try their best to keep their extended arm still (even if it means holding one's wrist with their other hand) and make sure that whatever measurement they are referring to goes from the top of their thumbs fingernail to the top of their measuring tool.¹ Because of the inconsistencies in measuring it is necessary to check one’s measurements multiple times while trying to be as precise as possible about them and going with the measurement they find most often.¹ Please note that the colored lines that appear in these photos were not on the Bargue while I was drawing. I used a knitting needle to measure and check alignments. And the horizontal line on my drawing that represents the halfway mark was made with a level to ensure its accuracy.

When drawing a cast one can’t really place their measuring tool on the cast to find the halfway point but one certainly should place their measuring tool on the drawing to ensure that their measuring and aligning is accurate. To do this properly one has to make sure that they are looking at the extremity of each measurement at eye level. For instance, when I was finding the halfway mark on my drawing I made sure to look at the top and bottom of the measurement on my knitting needle at eye level to make sure that I had a constant measurement.¹ I have found it more useful to mark a line on my knitting needle when trying to find these measurements instead of using my thumb. But there is no remedy for this when measuring the cast. One just has to try their best to keep their extended arm still (even if it means holding one's wrist with their other hand) and make sure that whatever measurement they are referring to goes from the top of their thumbs fingernail to the top of their measuring tool.¹ Because of the inconsistencies in measuring it is necessary to check one’s measurements multiple times while trying to be as precise as possible about them and going with the measurement they find most often.¹ Please note that the colored lines that appear in these photos were not on the Bargue while I was drawing. I used a knitting needle to measure and check alignments. And the horizontal line on my drawing that represents the halfway mark was made with a level to ensure its accuracy.

Block-in Step 5- Alignment of Quarters

I now aligned the shapes in my drawing to the quarter marks

on the Bargue. The placement of the initial

big shapes that I put in during step 3 were not too far off so I just used a rolled kneaded eraser to lighten

my initial shapes and re placed them.

But in a situation where the initial shapes are found to be very off

while checking these measurements it is useful to just roll out the initial

shapes with a kneaded eraser, mark off notations of where the shapes now have

to be placed and then re draw them.¹

Note that I am still only using the initial shapes that I

started with. This is because much of

blocking in is about accuracy of the big shapes. Only after I have checked the height to width

and alignment of the drawing do I have the confidence to add more tilts to those shapes.¹

Block-in Step 6- Flipping a dimension

This is the step prior to checking my height to width

measurement. To get a clue as to which

side of my drawing is more off and will most likely have to change to make my

height to width work I flip the longest part of the longest dimension that can be flipped into the

shorter dimension. In this instance, I

flipped the halfway measurement instead of the quarter measurement because the

halfway is long enough to be flipped for it to cross over when checked from the

left and right side on the Bargue. If I

was to flip a quarter, which is not long enough to cross when checked from the

left and right side, I could get the quarters to work well in my drawing and

not be certain of the space in between them.¹

In this instance, I found that the halfway measurement of the height flipped

into the width was much more accurate in my drawing when flipped from the the right side than the left

side. This gave me an idea that the left

side of my drawing may have to move to the right so the halfway flipped from

the left side can touch where it is supposed to.

This guess was confirmed when I checked how the width of

the Bargue flipped into the height of the Bargue. I noticed that the width flipped into the

height on my drawing was much longer than it was supposed to be. I flipped the width into the height from the

top and bottom of the Bargue but in this photo I am just showing the width

flipped from the bottom of the Bargue.

Block-In Step 7- Height to Width

I now moved the left side a bit to the right which made the

halfway flipped from that side touch where it was supposed to and shortened the

width of my drawing so that the width flipped into the height on my drawing

touched where it was supposed to. Overall,

the decision to move a shape should also be based upon seeing it in the animal

shapes and in this instance it did seem like the shape of the left earlobe, that I saw as a snake, could move to the right

so I changed it. One can trust the

relationship of the shorter dimension flipped into the longer dimension if they

have properly aligned the shapes to the halfway and quarter marks in the longer

dimension.¹

Block-in Step 8- Anchor Plumb

The final step of comparative measurement is what Jeremy Deck calls the "anchor

plumb".¹ This stage is to make sure that

even after a proper height to width measurement has been defined that the shapes within are properly aligned.¹ To do this

one must flip a part of the longest dimension into the shorter dimension and

plumb it through the longest dimension.¹ It

is useful to use an anchor plumb that runs through a lot of information on

what one is copying.¹ In this instance, I

flipped a quarter of the longest dimension from the left side of the Bargue. To see how the shapes related to this plumb

on the Bargue I held the point of my knitting needle in between my fingers and

let it dangle which allowed gravity to place it completely vertical.¹ On the drawing I just used a level to make

sure that it plumbed completely vertical.

I then re-organized my shapes around this plumb line. After this one can check the alignment of 1/8th’s

on the longest dimension and can flip the measurements of the 1’4’s and 1’8’s

into the shorter dimension if they want to.

Step 9- Alignment, Angles, Animals

After the anchor plumb is established one can focus completely on the

alignment and angles of the animal shapes without worrying too much about

measuring because the measuring previously used should have properly placed key

points in the drawing.¹ As long as these

key points do not move the block-in can be adjusted without fear of losing

accuracy.¹ Please note, that because there is room for error with measuring the animal shapes are the greatest guide at this point because in the end the

eye is more accurate than any measuring device.¹

To this end, if the shapes seem to need to move beyond the measured

marks a bit it usually is fine as long as they don’t go too far beyond the

measured marks.¹ After the anchor plumb

stage the broad lines can be broken into smaller tilts, while thinking of

adding tilts as adding character to the animal shapes, and using thinner lines to be

more specific.¹ The general rule is to work from general to specific. So the thinness of the line is to correspond to the amount of tilts and shapes that are in the drawing.¹ Also, it is a good idea to make sure that no part of the block-in is advancing too far beyond other parts because it would make it too difficult to compare the different areas that one is working on.¹ (The only exception to this rule is in drawing the figure because it is fine for the drawing of the torso to advance beyond other parts since the torso is the part of a figure that moves the least and the development of other areas should be based around it.) It can be very helpful to

switch to a rubber eraser to thin the line.

The Tombo Mono Zero is a great thin rubber eraser and can be purchased here http://www.jetpens.com/Tombow-Mono-Zero-Eraser-2.3-mm-Circle-Silver-Body/pd/1747 And it can be helpful to lighten a previous attempt by using a rolled

kneaded eraser to roll it out and then try again more specifically with the

pencil on top of it. I find it useful to

plumb just about everything in this stage before thinning my line too much.

Also, after the "anchor plumb" stage it is very useful to think of how the animal shapes relate

to each other by imagining how the different animal shapes are interacting with

each other and checking to see if the same is happening in one’s drawing.¹ Another useful tip is to quickly turn one’s

head from a shape on the Bargue to a shape on the drawing to see if it is

animating or moving more or less than it is supposed to.¹ When drawing a cast with comparative measurement, although the block-in started at an arms length away from the eye by this step the easel is much closer and by the final pass step the front of the easel is to be touching one's feet so one can have a clear view of what they are drawing.¹ When drawing this close the drawing board must be raised or lowered from its original placement so that what one is drawing is at the center of their cone of vision.

Step 10- Final Pass (Conceptual Thinking)

In this stage one focuses more on the three dimensional

reality that the shapes describe. It is

to be thought of as reaching into the picture plane, placing the point of one’s

pencil on the form and running it across the side of the form that the shapes

describe to discover how much the form is advancing and receding in space. One should draw the conceptual pass using the

lines that were made while discovering the placement of the shapes as a

guide.¹ Because it is easy to exaggerate

tilts in this stage it is necessary to check the results of the conceptual pass to animal

shapes to make sure that one is not exaggerating tilts. It is still crucial to use straight lined

even in this stage. It is very difficult to decide on the amplitude of each curve when trying to draw it all

at once so it becomes useful to break up curves into small straight lines as

if the lines were planes in space.¹ The advanced student can apply conceptual

thoughts of anatomy and perspective into the conceptual pass at this stage but

since I am a beginner I only go as far as thinking about planes advancing and receding

in space during the conceptual pass. It

is only when a student has attained a high skill level with measuring and

animal shapes that they can move to anatomical thinking during the conceptual

pass to ensure that their knowledge of anatomy will properly conform to the

visual shapes that one sees. In the end,

knowledge of anatomy is very important, especially for modeling form, and if

one does not immerse themselves in the study of anatomy they can reach a limit by only copying shapes.

Below are some block-ins that I have taken to the conceptual pass stage. Please note, that the light shading of the shadows in these studies was done as a last step. By shading in the shadows the light shapes appear bigger than they actually are. So to give me a greater potential for accuracy in blocking-in I shade the drawing in as a last step and it is only to make the block-in easier to look at. It does nothing to make the block-in more accurate. Also note that for this post and future posts that some of the work that I

have made at school have small areas that my instructors have drawn on

for demonstration purposes.

Tippy casts are a great way to practice

comparative measurement because the shapes become so unfamiliar to a

preconceived understanding of anatomy that one has to focus on the character of

the shapes before them to attain any accuracy. These block-ins were each worked on for a

couple of hours. Jeremy Deck reccomends practicing comparative measurement on cast drawings at life size . So when determining the measurement of the longest dimension when beginning a drawing one can actually place a knitting needle on the cast to ensure that the measurement of the longest dimension is life size.¹ Below are some examples of some tippy casts that I have done.

Blocking in the figure uses the same method of comparative measurement that I have described in the Bargue demonstration. The only difference is that it is very helpful to use the shape of the torso to start because since a figure moves the part of the body that moves the least is the torso. So it is very helpful to get the torso as accurate as possible first and then move out from there.¹ For example, in this figure Bargue copy the first shape that I drew was the shape of the torso.

Below are some of the figure Bargues that I have done.These figure Bargues are just for the practice of seeing how close one can get the animal shapes and measurements within a short time frame so all of these figure Bargues (except for the first one) were done between 4 and 4.5 hours. The timing system that I usually use for these is as follows.

-5min- Envelope and Rythms

-20min- Big Shapes

-20min- Halfway Alignment

-30min- Alignment of Quarters

-30-45min-Height to Width Reorganization

-30min- "Anchor Plumb"

-30min- Alignment of 1/8's

-1hr- Adding tilts

Please note, that because these figure bargues are much too large to be seen in one cone of vision it is useful to place it at a perpendicular angle to one's gaze while copying them. Jeremy Deck (personal communication, 2012) recommeds propping the Bargue on a few pieces of cardboard.

Comparative measurement can also be practiced in a sketchbook through the use of a measuring stick that one can mark measurements on in place of a knitting needle. If this measuring stick has edges that are perpendicular then vertical and horizontal plumbs can be obtained by making sure that the top or side of the measuring stick is parallel with the vertical or horizontal extremities. If the measurement of the longest dimension on the Bargue and on one's copy is the same then the after the block-in is complete its accuracy can be checked on a light box. Or if one does not have a light box the block-in can be checked by overlapping the Bargue and the copy in Photoshop.

Footnotes

¹ Jeremy Deck, personal communication, 2012.

² Andrew McManus, personal communication, 2013.

3 comments:

great post!

and great explanations

thank you for taking the time to put it down! is an enormous amount of information!

Step 2 is planarization and Step 3 is marbling.

although its clear and concise explanation a visual explanation would be more beneficial to demonstrate the principal.(pleeeeeeease)

(perharps on the sphere or on your superb ear modelling)

well done a master in the rising.

Thanks for your nice comments. I did not take process photos of my ear cast drawing that exemplify the transition from planarization to the marble. But Scott Waddell provides a great visual example of this transition in his Webisode 6.

It can be viewed here starting at 4:17.

The transition is really just about breaking down the large planes from the planarization stage by pushing and pulling microplanes in graphite towards or away from the white of the paper to suggest a subtle and accurate description of how the form turns towards and away from the light source.

I hope this answers your question. If not just let me know and I can draw another sphere with photos of the transition from planarization to the marble.

Post a Comment